by lspeed | Nov 20, 2025 | KNOWLEDGE: MEAT ESSENTIALS

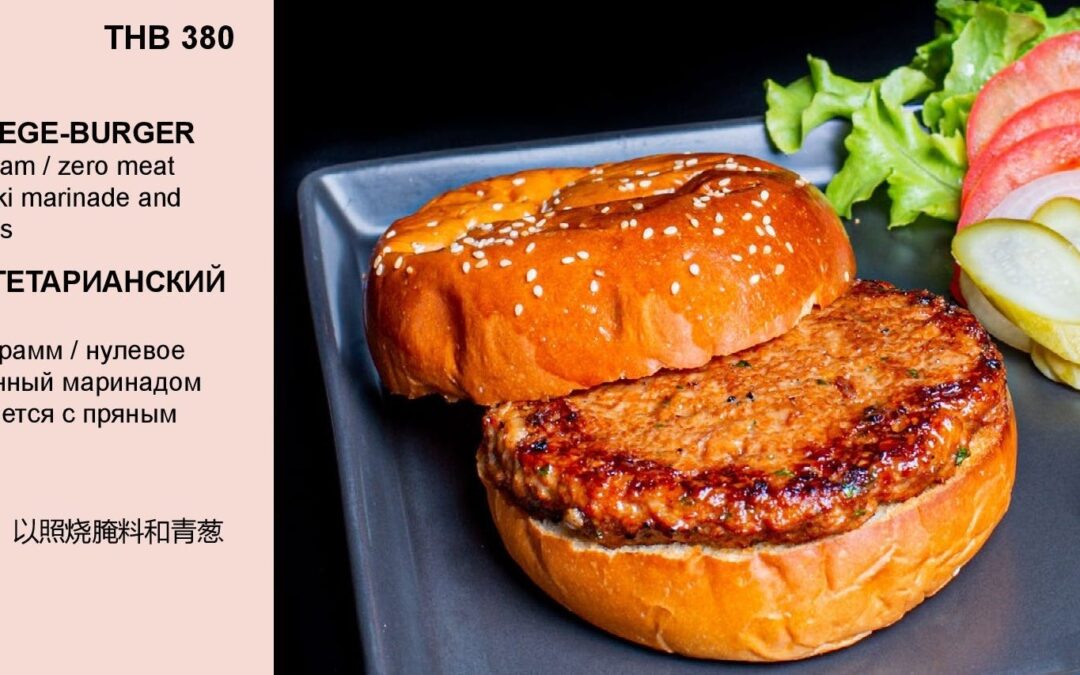

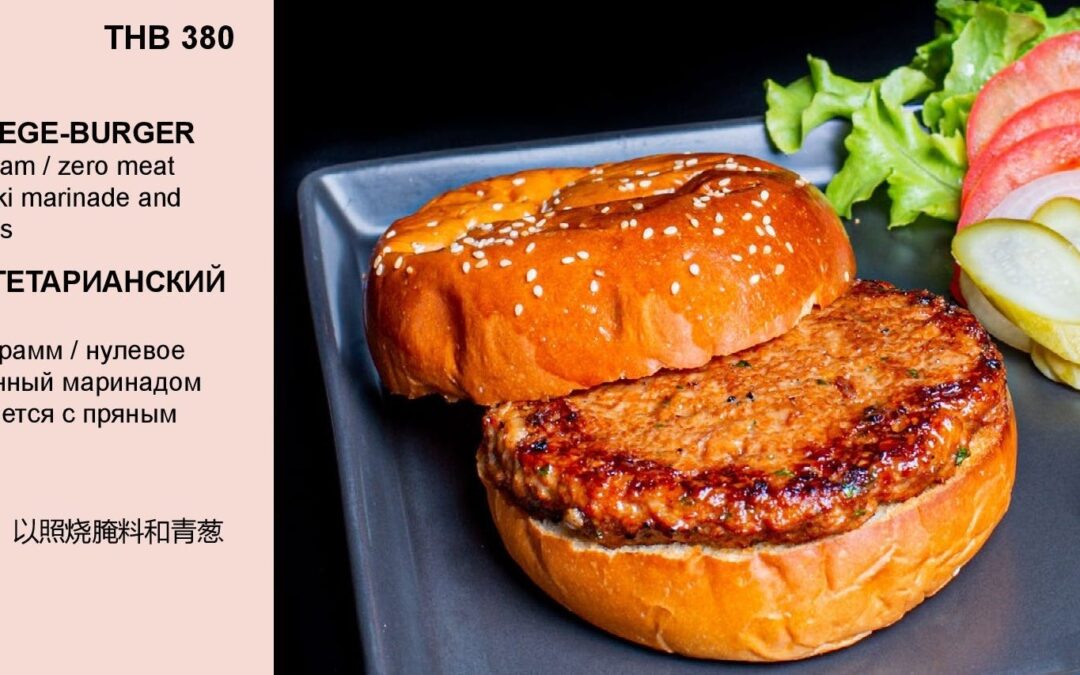

The rapid rise of plant based meat substitutes has been one of the more discussed food industry developments over the past decade. At Churrasco Phuket Steakhouse, we decided to add a plant based burger to our Gourmet Burger line-up during the height of the trend. The results became clear quite quickly – we sold roughly one plant based burger per month while consistently serving more than two hundred of our well known affordable Wagyu burgers in the same period.

Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat positioned themselves as disruptive forces that would redefine how people eat. Their early marketing leaned heavily on technological framing and strong environmental messaging. Early predictions assumed these products would move from novelty to widespread adoption. Today, the industry picture is more measured. Revenues are falling, several smaller brands have exited the market and valuations have declined sharply.

Impossible Foods private share value has dropped by close to ninety percent since 2021, to which they responded by undertaking a complete rebrand. The company will move from green packaging to red in an effort to appeal directly to consumers who associate red with appetite and meat. This shift signals a recognition that the original brand identity did not resonate with the broader consumer market.

From our steakhouse operator standpoint, the mismatch has been visible for some time. The early excitement around plant based meat was driven by media attention, “FOMO” investment enthusiasm, and a vocal group of early adopters from the woke spectrum of society.

However, the dining public does not behave in the same way as the promotional cycle. The difference between projected market penetration and actual purchase behaviour reflects several practical barriers that most food service operators have long understood.

Price

Plant based substitutes often cost significantly more than traditional beef. In grocery retail, that difference is easy for consumers to see. In restaurants, the gap becomes even more pronounced. Guests intuitively evaluate value. When a plant based patty is priced close to a traditional steak or to a premium beef burger, very few customers feel compelled to choose it unless they have specific dietary preferences.

Demographics

Research consistently shows that plant based substitutes appeal primarily to younger, urban and higher income consumers. That group is often open to experimentation, but it does not represent the full restaurant market. The typical steakhouse guest spans a much broader set of ages and preferences. Many come precisely because they want a traditional experience built around beef. For them, the appeal of a plant based replica is limited, and rarely repeat driven.

Messaging

A sizable share of plant based marketing relied on moral framing. The suggestion, at times, was that choosing conventional meat was outdated or irresponsible. This approach created unnecessary resistance. Guests do not want dining decisions to be turned into political or cultural statements. Food service success relies on trust, clarity and consistency, not on signalling.

Politics

Especially in the US, plant based products became entangled in cultural debates that had little to do with the actual food. Commentators on both extremes claimed symbolic meaning for these items, ranging from elitism to conspiracy. While such narratives are far removed from industry realities, they influence consumer behaviour. Once a product carries ideological weight, marketing adjustments such as packaging colour changes cannot meaningfully shift perception.

For restaurant operators, the practical takeaway is clear. Initial curiosity may drive trial, but long term adoption relies on habitual use, not on symbolic significance. Across the market, plant based trial rates were high, yet repeat purchase rates were low. Our own experience was consistent with this pattern. Guests were willing to try a plant based burger once, often out of curiosity. Very few returned to it. In contrast, our Wagyu burgers continue to sell at scale because they satisfy established expectations around flavour, texture and value.

Plant based items should not necessarily be excluded from steakhouse menus. Operators still offer them as a courtesy for guests with dietary restrictions or preferences. When presented as a simple menu option rather than as a philosophical statement, these items can serve a practical purpose. The key understanding is that they are supplementary, not transformational.

Image Credit: https://churrascophuket.com

_ _ _

© CHURRASCO PHUKET STEAKHOUSE / ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Reprinting, reposting & sharing allowed, in exchange for a backlink and credits

Churrasco Phuket Steakhouse serves affordable Wagyu and Black Angus steaks and burgers. We are open daily from 12noon to 11pm at Jungceylon Shopping Center in Patong / Phuket.

We are family-friendly and offer free parking and Wi-Fi for guests. See our menus, reserve your table, find our location, and check all guest reviews here:

https://ChurrascoPhuket.com/

#Churrascophuket #jungceylon #phuketsteakhouse #affordablewagyu #wagyu

by lspeed | Nov 9, 2025 | KNOWLEDGE: MEAT ESSENTIALS

First up – established and reputable restaurants such as Churrasco Phuket Steakhouse would rather go full-time vegan instead of EVER serving fake Wagyu. Our reputation and long term survival rests on our authenticity, consistency, top quality and personal integrity. Every steak that reaches our tables comes from verified sources only.

Yet, not all establishments in Asia share the same standards. A recent food scandal in Vietnam revealed how far some will go to imitate luxury beef.

FAKE WAGYU

In Hanoi, Vietnam, police recently arrested four people accused of turning cheap buffalo meat into fake Wagyu. They bought frozen buffalo from India for about four dollars a kilo, injected it with a “fat essence” to mimic Wagyu marbling, then relabelled it as premium “Hidasan Wagyu.” The meat sold for five times its cost. More than fourteen tons reached restaurants before investigators intervened. Tests confirmed most samples contained buffalo DNA. What began as food fraud soon became a public health matter.

The scandal shows how the demand for marbled beef fuels deception. Real Wagyu commands high prices because its marbling comes from genetics and patient feeding, not chemicals. Counterfeiters exploit that by mimicking its look. Some mislabel regular beef as Wagyu, others use injections or even different animals to fake its texture and price.

In the Vietnamese case, all tricks appeared together: wrong species, chemical marbling and false branding. Counterfeiters know that many diners cannot tell imitation from the real thing. once it is sliced and grilled. The marbling alone convinces most people.

Yet true Wagyu has a distinct aroma, flavour and softness that are impossible to reproduce. The case also showed the risk behind imitation. Injecting chemicals into meat deceives buyers and threatens health. Regulators are still studying what substances were used, but the lesson is clear: trust only restaurants that value transparency.

LARDED BEEF

Between fraud and true Wagyu lies the grey zone of “larded” or artificially marbled beef. These products are legal and widely sold, but they should never ever be mistaken for genuine Wagyu. Brands such as Meltique and Hokkubee use fat injection to give standard beef a marbled look and tender texture. The technique came from an old French method called piquer, where strips of fat were inserted into lean meat.

Meltique injects an emulsion of beef fat or canola oil into muscle fibres, creating uniform marbling though the cattle were not Wagyu. It looks appealing, cooks easily and costs far less. Hokkubee, the company behind Meltique, promotes it as a consistent and affordable option for restaurants.

There basically is nothing illegal with this process – but only when declared openly. Restaurants absolutely must identify Hokkubee and similar larded products clearly. Unfortunately, some restaurateurs fail to do so, letting guests assume they are eating Wagyu when they are not. Larded beef may look luxurious, but it cannot match the sweetness, melt or grain of real Wagyu. Technology can create texture, not heritage.

For clarity, Churrasco Phuket Steakhouse has never ever served or will serve this product.

REAL WAGYU

True Wagyu comes from Japan’s long tradition of cattle breeding. The word combines “wa,” meaning Japanese, and “gyu,” meaning cow. It refers to breeds such as Japanese Black, Brown, Shorthorn and Polled, raised under strict care. These cattle are bred to store fine layers of fat that create the lace-like marbling running through the meat.

Each animal is raised slowly, often fed on rice straw, barley and grain, and tracked from birth. The highest grade, A5, represents exceptional marbling and tenderness. The fat melts at low temperature, releasing a clean sweetness when cooked.

Japan is the birthplace of Wagyu, but Australia has also built a respected Wagyu industry. Many Australian herds descend from Japanese bloodlines and are raised on similar feeding programs. The result is beef that retains lush marbling and excellent consistency. Both Japan and Australia now set the global standard for quality and traceability.

SPOTTING THE DIFFERENCE

To identify real Wagyu, start with documentation. Authentic Wagyu is always delivered with information on the breed, farm and grade. Any beef labelled “Wagyu style” without such details should immediately raise doubt. Real Wagyu marbling is fine and even, glowing softly pink. Fake or larded beef often shows thicker white streaks or uneven patches. When cooked, genuine Wagyu melts smoothly and releases a delicate aroma, while imitations exude oil and taste heavy.

Price can also tell at least part of the story. If something is too cheap to be real, it almost certainly is. A steak that looks like Wagyu but sells cheaply is rarely authentic. Real Wagyu is expensive because it takes time and care to produce.

PROTECTING OUR GUESTS

No credible establishment would risk its name or guests’ health by serving fake or chemically altered beef. We at Churrasco Phuket Steakhouse make categorically sure that our guests can dine with confidence. Every one of our Wagyu steak cuts, whether our Picanha, Maminha, Solomillo or Tenderloin, comes from verified herds and fully certified suppliers. Our restaurant’s international reputation for value and quality depends on that trust.

Everywhere else though, your best protection is prudent scepticism and raised awareness. Ask the restaurant about the beef’s origin and supplier. Restaurants with integrity are proud and totally open to answer any such questions. Remember also that real Wagyu is more than flavour. It is patience, precision and transparency. Every certified Wagyu carries proof of origin and grade. When you buy it, you pay for that history as much as the taste.

The Vietnamese scandal is a reminder of what happens when profit overtakes honesty. True Wagyu remains the peak of beef craftsmanship, and the best restaurants treat it with respect. In a world full of marbled illusions, diners can rely on restaurants like Churrasco Phuket Steakhouse to serve only the real thing, prepared with care, honesty – and pride.

Image Credit: hhttps://meatstock.com.au/australian-wagyu-association/

_ _ _

© CHURRASCO PHUKET STEAKHOUSE / ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Reprinting, reposting & sharing allowed, in exchange for a backlink and credits

Churrasco Phuket Steakhouse serves affordable Wagyu and Black Angus steaks and burgers. We are open daily from 12noon to 11pm at Jungceylon Shopping Center in Patong / Phuket.

We are family-friendly and offer free parking and Wi-Fi for guests. See our menus, reserve your table, find our location, and check all guest reviews here:

https://ChurrascoPhuket.com/

#Churrascophuket #jungceylon #phuketsteakhouse #affordablewagyu #wagyu

by lspeed | Oct 12, 2025 | KNOWLEDGE: MEAT ESSENTIALS

Japan’s Wagyu is a symbol of indulgence, with marbled textures and melt-in-the-mouth flavors that command some of the highest prices in the culinary world. Yet even within Japan’s Wagyu tradition, three names stand out – Kobe, Matsusaka, and Miyazaki. Each hails from a different region, each has a distinct reputation, and each carries its own market value.

Kobe Beef

Kobe beef originates from the Hyōgo Prefecture and must come from purebred Tajima-gyu cattle, a line of Japanese Black Wagyu. Strict rules govern what qualifies as “Kobe”. The cattle must be born, raised, and slaughtered in Hyōgo, and only steers (castrated males) or virgin heifers are eligible. Because of this limited geography and controlled lineage, Kobe is not just a brand but a certification.

Matsusaka Beef

Matsusaka beef is raised in Mie Prefecture, primarily from female cattle that have never calved. Unlike Kobe, where steers dominate, Matsusaka is known for its pampered virgin cows. Farmers are famed for their meticulous care, feeding blends of rice straw, barley, and occasionally beer, while brushing the animals to improve circulation. This regimen contributes to ultra-fine marbling and tenderness, cementing Matsusaka’s reputation among Japanese gourmands as perhaps the most luxurious Wagyu.

Miyazaki Beef

Miyazaki beef comes from Miyazaki Prefecture in Kyushu and has risen in prominence more recently than Kobe or Matsusaka. While Kobe leans on centuries of tradition, Miyazaki has built its reputation on excellence in cattle breeding and feeding programs. Miyazaki beef consistently wins national Wagyu competitions, including the coveted Prime Minister’s Award, and is now considered the strongest rival to Kobe in global markets.

Grading Standards

All three Wagyu types follow Japan’s national grading system established by the Japan Meat Grading Association (JMGA). Beef is graded on two key axes:

-

Yield Grade (A, B, C): A measures carcass yield relative to weight, with A being the highest.

-

Meat Quality Grade (1–5): Evaluates marbling, meat color, brightness, firmness, and fat quality.

-

Within this, the Beef Marbling Score (BMS), ranging from 1 to 12, further defines quality.

-

Kobe Beef: Only carcasses graded A4 or A5 with a BMS of 6 or above qualify as Kobe. This sets an extremely high entry bar, which explains why less than 3,000 heads per year receive Kobe certification.

-

Matsusaka Beef: Typically graded at the highest levels, with many examples exceeding BMS 10–12. Matsusaka holds its own branded grading competitions, and “Matsusaka Grand Champion” carcasses often fetch record prices.

-

Miyazaki Beef: Consistently achieves A5 grading and has built a reputation as the most reliable in maintaining top scores across large production volumes. Miyazaki beef has won consecutive titles at Japan’s Wagyu Olympics, a feat unmatched by any other region.

Flavor and Texture Differences

A Hard Choice

All of these three Wagyu types sit at the summit of Wagyu culture, but they each tell a different story. For diners, the choice often comes down to budget, and whether they seek the prestige of Kobe, the richness of Matsusaka, or the balance of Miyazaki.

Image Credit: https://www.vecteezy.com/free-photos/japanese-wagyu

_ _ _

© CHURRASCO PHUKET STEAKHOUSE / ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Reprinting, reposting & sharing allowed, in exchange for a backlink and credits

Churrasco Phuket Steakhouse serves affordable Wagyu and Black Angus steaks and burgers. We are open daily from 12noon to 11pm at Jungceylon Shopping Center in Patong / Phuket.

We are family-friendly and offer free parking and Wi-Fi for guests. See our menus, reserve your table, find our location, and check all guest reviews here:

https://ChurrascoPhuket.com/

#Churrascophuket #jungceylon #phuketsteakhouse #affordablewagyu #wagyu

by lspeed | Oct 5, 2025 | KNOWLEDGE: MEAT ESSENTIALS

Mention Beef Wellington, and it immediately signals ceremony. Its roots, however, are less precise than its polished presentation suggests. The dish first became associated with Britain in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Some food historians argue it was named in honor of Arthur Wellesley, the 1st Duke of Wellington, after his victory at Waterloo in 1815. The parallel between the duke’s strong, protective military image and the beef encased in pastry armor has long been part of the lore.

Others trace the dish’s ancestry to French and Russian kitchens. Variations of meat wrapped in pastry were already common across Europe in the 18th century. The French pâté en croûte, or Russian kulebyaka, bear a striking resemblance, suggesting Beef Wellington was less a singular invention than an adaptation that the British later claimed as their own.

Big Name Chefs

Though its origins are murky, the dish’s rise to prominence is easier to track. In the 20th century, Beef Wellington gained prestige through appearances at high-profile events and in the work of celebrated chefs. Delia Smith included it in her influential cookbooks, cementing its reputation among ambitious home cooks in Britain. In the United States, Julia Child and James Beard helped bring it into the culinary mainstream during the 1960s and 1970s, when it became a fashionable centerpiece for dinner parties.

More recently, Gordon Ramsay has been one of its more visible champions. His television series and restaurant menus made Beef Wellington synonymous with high-end modern dining. Ramsay’s interpretation, involving precise timing and a streamlined method, reintroduced the dish to younger chefs and audiences who might otherwise have dismissed it as outdated.

The Method

At its core, Beef Wellington is a lesson in balance and timing. A whole beef tenderloin is seared to develop flavor and seal in juices. A layer of finely chopped mushrooms cooked down to a paste is spread over the beef, sometimes with Foie Gras or pâté for richness. To prevent sogginess, some chefs use a thin crêpe or slices of prosciutto between the beef and pastry. Finally, the meat is wrapped in puff pastry and baked until golden.

The method requires precision: the beef must emerge medium rare while the pastry remains crisp. Achieving this balance has long been both the challenge and the allure for professionals. In restaurant settings, the preparation can be scaled, with individual Wellingtons prepared as single portions, or the classic whole roast sliced tableside for drama.

Classic Appeal

For the trade audience, Beef Wellington offers advantages. First, the high visual impact of the golden crust, cross-section layers, and dramatic carving make it a natural showpiece for special occasions. Second, the dish is adaptable. While the tenderloin remains traditional, chefs have experimented with lamb, venison, salmon, and even vegetarian versions using root vegetables or lentils. The method allows for seasonal interpretation and modern twists without losing its core identity.

Operationally, Wellingtons can be prepared ahead of service, held chilled, and baked to order. This staging makes it attractive for banquets and festive menus, reducing last-minute stress in the kitchen. Its association with celebration also gives restaurants a reliable upsell during holidays or set menus.

Going Forward

After peaking in the 1970s, Beef Wellington faded somewhat, seen as heavy or old-fashioned during the lighter dining trends of the late 20th century. Yet it has never totally disappeared. Over the past two decades, television exposure, social media, and the rise of “classics reimagined” menus have returned it to relevance. Diners value both the tradition it represents and the craft it demands from chefs.

Today, Beef Wellington sits comfortably in the space between heritage and innovation. A rare mix that explains why it still finds a place on fine dining menus worldwide.

Image Credit: https://wikipedia.org

_ _ _

© CHURRASCO PHUKET STEAKHOUSE / ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Reprinting, reposting & sharing allowed, in exchange for a backlink and credits

Churrasco Phuket Steakhouse serves affordable Wagyu and Black Angus steaks and burgers. We are open daily from 12noon to 11pm at Jungceylon Shopping Center in Patong / Phuket.

We are family-friendly and offer free parking and Wi-Fi for guests. See our menus, reserve your table, find our location, and check all guest reviews here:

https://ChurrascoPhuket.com/

#Churrascophuket #jungceylon #phuketsteakhouse #affordablewagyu #wagyu

by lspeed | Sep 21, 2025 | KNOWLEDGE: MEAT ESSENTIALS

Ask five carnivores if they prefer their steaks on or off the bone, and you’ll get ten different answers and reasons. Each defended with the kind of passion normally reserved for politics or football. The argument seems simple on the surface. Proponents of bone-in steaks swear that the presence of bone somehow adds extra flavor, juiciness, and character to the meat. Others, equally convinced, argue that bone is a romantic distraction, one that makes little difference in taste but a big difference in what ends up on the bill.

The Flavor Argument

Bone-in supporters usually cite two main claims. First, they believe that the marrow inside the bone somehow seeps into the steak during cooking, enriching the flavor. Second, they insist the bone acts as an insulator, slowing down cooking and keeping meat juicier. These ideas sound appealing, but food science tells a different story. Bones are dense, and marrow does not migrate into the muscle during the relatively short cooking time of a steak.

What the bone does do is block heat, creating an uneven cooking surface. This can leave meat near the bone less done than the rest, a detail some diners appreciate, but others find frustrating. In blind tastings we conducted over the years, people always struggle to identify whether a steak was cooked bone-in or boneless. In other words, much of the “flavor difference” comes down to presentation, perception and tradition, not measurable results.

The Value Question

Where the debate becomes more practical, and more important to us as a restaurant, is in the “value for money” part. Ordering a Ribeye “on the bone” means paying a premium steak price for what is an inedible piece of bone. It might look dramatic on a plate, but the fact remains that you cannot eat it. The extra weight you are charged for is not steak, it’s suited for soup stock or frankly, a dog’s dinner.

Guests may feel they are indulging in a more “authentic” experience, but economically they are receiving less edible meat per gram, despite paying more. For us, this crosses a line. Our philosophy at Churrasco Phuket Steakhouse has always been to provide maximum quality and value. We want every Baht spent by our guests to go directly into what they can enjoy, not what ends up on the plate or – yes – in a “doggie bag”.

Why We Serve Only Boneless Cuts

You won’t find Tomahawks or other bone-heavy cuts on our menu. We prefer to serve clean, boneless portions – Ribeye, Tenderloin, Picanha, Oysterblade, Sirloin, etc. These cuts deliver pure eating pleasure without any waste. By eliminating the theatrics of large bones, we focus instead on what truly matters: the sourcing of prime beef, expert aging, precise grilling, and consistent doneness.

These are the factors that shape guest enjoyment far more than whether a bone happens to be attached. Our guests come to us knowing that when they order 300 grams of Wagyu Ribeye, they get 300 grams of Wagyu Ribeye that will not cost them an arm and a leg. That transparency is central to our identity and success as Phuket’s most affordable quality steakhouse, and has served us well over the 13 years we have been in operation.

Image Credit: https://churrascophuket.com

_ _ _

© CHURRASCO PHUKET STEAKHOUSE / ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Reprinting, reposting & sharing allowed, in exchange for a backlink and credits

Churrasco Phuket Steakhouse serves affordable Wagyu and Black Angus steaks and burgers. We are open daily from 12noon to 11pm at Jungceylon Shopping Center in Patong / Phuket.

We are family-friendly and offer free parking and Wi-Fi for guests. See our menus, reserve your table, find our location, and check all guest reviews here:

https://ChurrascoPhuket.com/

#Churrascophuket #jungceylon #phuketsteakhouse #affordablewagyu #wagyu

by lspeed | Sep 7, 2025 | KNOWLEDGE: MEAT ESSENTIALS

One of Germany’s national dishes, Sauerbraten is a marinated pot roast typically made with beef, although versions with horse meat, pork, or venison exist in different regions. The name translates literally to “sour roast,” referring to the extended marination in a vinegar-based mixture that defines the dish’s character.

This sour-sweet flavor profile, paired with slow braising, makes Sauerbraten a distinctive expression of German culinary tradition. Its origins are somewhat obscure, though it is widely believed to have roots in the Roman Empire. Some food historians suggest the technique of preserving and tenderizing meat in acidic liquids could have been passed down through Roman occupation of the Rhineland.

One popular, albeit unverified, legend credits Charlemagne with conceptualizing Sauerbraten as a way to use leftover roast. More likely, Sauerbraten evolved during the Middle Ages as a way to make tougher cuts of meat palatable and extend their shelf life in the absence of refrigeration.

By the 13th century, the use of vinegar and wine as preserving agents became commonplace in Germanic cooking, especially for game meat. Sauerbraten eventually emerged as a celebratory dish, served at Sunday tables, weddings, and festivals across the German-speaking world.

Preparation

Sauerbraten’s preparation begins with a long marination period—typically three to five days—in a mixture of vinegar (often wine vinegar), red wine, onions, carrots, celery, bay leaves, peppercorns, juniper berries, and cloves. This mixture not only tenderizes the meat but also infuses it with deep, aromatic flavor. After marination, the meat is browned, then braised in the same liquid until fork-tender.

The sauce, another hallmark of the dish, is thickened using gingersnap cookies, Lebkuchen (a type of spiced German biscuit), or sometimes roux. These additions balance the acidity of the marinade with subtle sweetness and spice, yielding a rich, complex gravy. Sauerbraten is traditionally served with potato dumplings, red cabbage, or boiled potatoes. The combination of sour, sweet, and savory elements is emblematic of central European taste.

Popularity

While Sauerbraten is widely associated with Germany, regional variants abound. In the Rhineland, for example, sugar or raisins are added to the marinade for a sweeter version, while in Franconia, the dish is more vinegary and dry. Swabia leans toward a more wine-forward preparation, and in Saxony, beer sometimes replaces part of the marinade liquid.

Sauerbraten also traveled with German immigrants. In the United States, especially in Pennsylvania Dutch communities, it remains a celebrated holiday dish. German-American restaurants often feature it as a nostalgic anchor for older generations seeking the flavors of home.

Though less globally ubiquitous than other European dishes, Sauerbraten retains an enduring popularity in Germany and among enthusiasts of traditional European cuisine. It symbolizes comfort, heritage, and culinary patience—a slow dish in a fast world.

Purpose

Historically, Sauerbraten served both economical and practical purposes. Tough, inexpensive cuts like rump roast, brisket, or even horse meat were made tender and flavorful through days-long marination. In pre-refrigeration times, the acidic marinade helped preserve the meat, allowing families to prepare large portions ahead of a Sunday feast or holiday meal.

Beyond its practicality, Sauerbraten’s sweet-sour flavor reflects a broader medieval and early modern European taste tradition—where the interplay of vinegar, sugar, and spice was fashionable, even in aristocratic kitchens.

Similar Dishes

Sauerbraten is far from the only dish that uses acidic marination followed by slow cooking. Across the globe, similar techniques have emerged, often driven by the same logic: transforming tough cuts into flavorful meals.

1. Bo Kho (Vietnam)

This aromatic beef stew is marinated in fish sauce, lemongrass, garlic, and spices before slow simmering. Though its flavor profile is different—more lemongrass and star anise than vinegar—it shares Sauerbraten’s commitment to bold, marinated flavor and slow tenderness.

2. Adobo (Philippines)

Perhaps the closest in technique, Filipino adobo involves marinating meat (usually pork or chicken) in vinegar, soy sauce, garlic, and bay leaves, followed by simmering. Like Sauerbraten, the acid not only tenderizes but becomes the base of the final sauce.

3. Civets (France)

Traditional French civets, such as “civet de sanglier” (wild boar stew), also use red wine and vinegar marinades with aromatics. These dishes often hail from the countryside and were designed to tenderize game meats. Like Sauerbraten, civets are both rustic and refined, reflecting deep regional roots.

4. Carne en Adobo (Spain/Mexico)

Derived from the Spanish colonial culinary legacy, adobo marinades typically involve vinegar, paprika, garlic, and oregano. While in Spain the dish might involve slow-cooked pork, in Mexico, adobo is often used with grilled meats or stews.

5. Escabeche (Mediterranean & Latin America)

This technique involves cooking fish or meat, then marinating it in a spiced vinegar solution. Though typically served cold and more delicate, escabeche shares the preservation-driven purpose of Sauerbraten’s original function.

6. Carbonnade Flamande (Belgium)

Using beer instead of vinegar, this dish features beef marinated and simmered in Belgian ale with onions and mustard. It’s a sweet-sour dish with a regional twist—closer to the Rhineland variant of Sauerbraten, albeit without the sharp vinegar base.

Image Credit: https://cookidoo.international/recipes/recipe/vi/r812359

_ _ _

© CHURRASCO PHUKET STEAKHOUSE / ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Reprinting, reposting & sharing allowed, in exchange for a backlink and credits

Churrasco Phuket Steakhouse serves affordable Wagyu and Black Angus steaks and burgers. We are open daily from 12noon to 11pm at Jungceylon Shopping Center in Patong / Phuket.

We are family-friendly and offer free parking and Wi-Fi for guests. See our menus, reserve your table, find our location, and check all guest reviews here:

https://ChurrascoPhuket.com/

#Churrascophuket #jungceylon #phuketsteakhouse #affordablewagyu #wagyu